Meet Dr. Alejandro Diaz Arumir – physician, humanitarian, and lifelong student of resilience. Here, he shares about his upbringing in Mexico, time working with Doctors without Borders, and the many experiences that have shaped who he is today.

Tell us more about yourself.

I am a physician from Mexico, a country of strong contrasts. When I was fourteen, my father was briefly kidnapped and returned home thanks to my mother’s courage and the support of friends, an early lesson in resilience and trust I guess. Later, working with Doctors Without Borders in Niger and Haiti, I saw suffering and hope side by side. I became a rheumatologist and learned how the immune system can heal or harm, and how much of medicine is about finding balance.

The person who has shaped me the most is my sister Edith, who has Down syndrome. Being her brother is my superpower; she taught me that what others call a limitation can be a different way of shining, and she made empathy the center of my life and my practice.

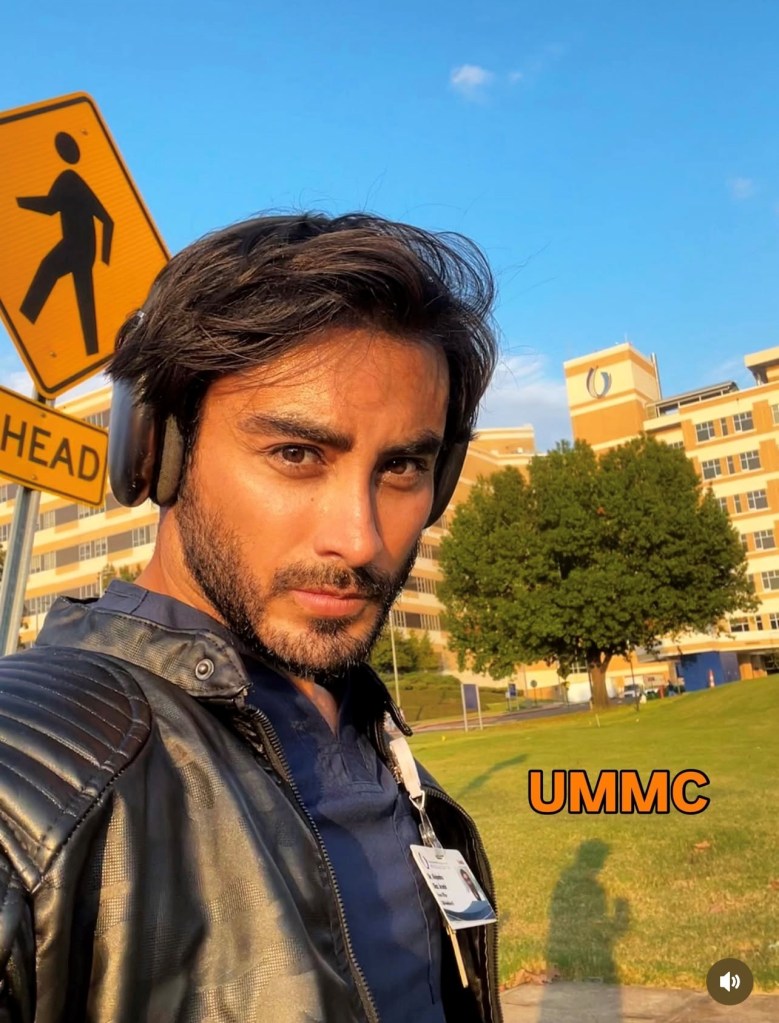

I’ve come to believe that it is in these contrasts that we decide who we are. Now, as an Infectious Diseases fellow at UMMC, I hope to bring that resilience, curiosity, and empathy to the patients and colleagues I meet here.

Why infectious diseases?

It probably started in Niger, during my time with Doctors Without Borders. I worked in a small ER for children with severe malnutrition and infections like malaria, TB, meningitis, and diarrheal diseases. Almost everything was improvised except hope. When a child recovered, it felt like a tiny part of the world had been repaired, and I realized medicine was, above all, an act of humanity.

Later, in my internal medicine residency, I was repeatedly drawn to patients with infections. I loved the detective work of ID and how a single detail in the story or the labs could change everything.

Then, COVID made it personal. At the beginning of the pandemic, my mother and sister became critically ill. My dad, my brother, and I had to make quick decisions based on emerging evidence, and I watched them slowly recover. That experience convinced me that this is where I want to be.

For me, infectious diseases is a trust: standing with patients at very vulnerable moments, using science to fight infection while also offering something just as important, to bring hope to the patients.

What do you like most about UMMC?

What I love most about UMMC is the genuine sense of belonging. From the very beginning—emails before I even arrived, the welcome meeting with the other fellows, smiles and greetings from staff and patients—I felt received not just as a physician, but as a person. There is a particular southern warmth here; people’s gratitude feels a little deeper, and it makes every long day worthwhile.

I’m constantly aware that I’m part of an institution whose work reaches far beyond these walls, both locally and globally. As an IMG, I feel deeply grateful to train at a place that has been a reference in infectious diseases, from mycoses to transplant medicine. Contributing even in a small way fills me with purpose.

What I treasure most is that I’ve never been made to feel like an outsider. My background in rheumatology is not only accepted, but valued. My supervisors treat me with kindness and trust, and that inspires me to give my very best. In just a few months, UMMC has given me not only knowledge, but clarity and confidence about the kind of physician I want to become.

On a more personal level, I was very moved by the movie “The Help”……being welcomed in this country, in this state, and in this city—Jackson, with its powerful civil rights history—moves me deeply. To serve this community as an ID fellow feels, in a small way, like continuing a story of dignity, acceptance, and shared humanity.

If you had to give a 40-minute presentation without preparation, what would you talk about?

I would talk about baking bread. It may sound simple, but for me baking is a mirror of perseverance and purpose. Bread is one of the most basic foods we share, yet there is something almost sacred in the process: the patience to wait, the humility to knead, and the faith to let something rise in its own time. You can’t rush yeast—just like you can’t rush growth, in life or in medicine.

Along my journey from Mexico to Canada and now the United States, from working with Doctors Without Borders to being an Infectious Diseases fellow, I’ve realized perseverance is a lot like baking. You start with simple ingredients, mix them with effort and hope, and, with pressure, heat, and time, something nourishing appears. Not every loaf turns out well, but even the “failures” teach you something.

Bread, in almost every culture, is about sharing. It represents life, abundance, and care for others. That’s also how I see medicine: not only as science, but as an act of feeding people’s trust, dignity, and hope. So yes, I would choose to talk about bread—for 40 minutes and probably more—because in learning to bake, I also learned to wait, to trust the process, and to believe that what we are nurturing will eventually rise, in its own time. And well… baking bread gives a sense of control, and even if the result is not as you wanted… it is not the end of the world.

What advice would you give to interns?

I would tell them first: don’t be afraid to ask questions. I used to be very shy and worried about bothering my teachers, so I stayed quiet too often. I’ve learned that asking with respect and clarity is always better than pretending you understand. There is no shame in not knowing.

Here at UMMC, I’ve appreciated how residents and students ask about ID with curiosity and respect. People respond to authenticity. Genuine empathy — not exaggerated, not forced — helps build trust with patients, nurses, and colleagues, and those relationships are a big part of our happiness in medicine.

I would also remind them that feeling lonely in this profession is more common than we admit. If they ever feel that way, they should know they’re not the only ones. Reach out. Ask for help. Honest vulnerability usually brings people closer, not farther away.

Finally, I’d share that being here at UMMC, after training in Internal Medicine and Rheumatology abroad, has taught me how important it is to believe that good things are possible and to feed hopeful, constructive thoughts. That mindset shaped many of my decisions. And if they ever have the chance to work with a humanitarian organization like Doctors Without Borders, I would strongly recommend it — it can change the way you see your patients, the world, and yourself.

What is something you wish you knew more about?

I wish I had understood much earlier the real power of gratitude.

Throughout my life I’ve met so many people who planted small seeds in me—teachers, colleagues, patients, strangers in different countries. Today I feel very blessed, and I know that a big part of what I have comes from what they gave me. But I also know that many of them will never hear me say “thank you” the way they truly deserved. We lost contact, or life moved us in different directions, and that opportunity is gone.

One of my strongest memories is from my first mission with Doctors Without Borders in Niger. I arrived thinking I was going there to give, but the people there gave so much to me. One day, a mother of one of my patients, who barely spoke French, handed me a Coca-Cola in the middle of the desert. It was such a small gesture, but it carried me through many lonely moments. At the time, I didn’t have the words—or maybe the awareness—to tell her how much that meant to me. I wish I had.

Over time I’ve learned that it’s not where you study or how “perfect” you are that defines you, but how you honor the moments and the people life puts in your path. If I could go back, I would be more present, squeeze a little more joy out of ordinary days, and say “thank you” more loudly and with authentic meaning… I didn’t know those times were my last chance to thank them.

So what I wish I had known earlier is simple: that gratitude is not just a feeling, it’s a way of living. To recognize that any moment can be the last time, and to tell people—while they are still here—how much they matter.

What are some small things that make your day better?

I mentioned baking bread… but meditation helps me the most. I’ll admit, it’s not always easy to start. Sometimes I’m already in bed and a little voice in my mind reminds me that I haven’t meditated yet. Laziness tempts me to stay where I am, but when I finally take even seven minutes — often with Hans Zimmer in the background — everything feels clearer.

Those few minutes remind me of what really matters: that my parents and my sister are still here, that I have many reasons to be grateful. It’s a small habit, but it changes my day. It gives me peace, perspective, and a quiet sense of gratitude.

Exercise also helps a lot — going to the gym, swimming, and honestly, a good night’s sleep. I wish I had understood the power of sleep earlier in my life. But meditation gives me something a little deeper: it reconnects me with life itself and with the awareness that, right now, I already have more than enough.

What is something about you that most people do not know?

Something few people know about me is that, as a child, there were parts of my life I kept quietly hidden — not out of shame, but out of love and protection. When my little sister Edith was born with Down syndrome, I felt an instinctive need to shield her from a world that could sometimes be unkind. I still remember how other children stared at her when my parents came to pick me up from school; I didn’t have the words for it then, but it felt as if my heart were walking outside my chest beside her.

There were also parts of my own identity that I kept guarded, afraid they wouldn’t be understood. With time, I realized that what once made me feel fragile is now what gives me strength. Protecting my sister taught me compassion; loving her taught me courage. Little by little, I stopped hiding my roots, my faith, my softness, even my “chubby boy” past — because I understood that acceptance doesn’t come from the outside, it starts within. I think that’s one of the reasons I became a doctor: to protect, to care, and to turn vulnerability into purpose.

And something people don’t usually expect: I once did a TV commercial in Mexico — maybe that’s where I first learned how to blend emotion with expression.

Thank you for the time and care you put into your fellow focus write-up. You shared wise words that have come from a breadth and depth of life experience that is well-lived. I was grateful to have you here at UMMC, and I know the ID team is grateful as well! Happy Holidays and blessings to you in the new year!

LikeLike